How Television Got to the NYSE Trading Floor

(A CEO’s approval; and why it’s important to the brand still today)

Some moments just stick with you. For life.

One of mine came about 25 years ago.

I had come back to the NYSE from Sony a year earlier, having re-joined the NYSE as Executive Vice President and a member of the Management Committee.

That first year back was spent travelling the world with then chairman Bill Donaldson. The future of the Exchange would come from non-U.S. listings and Bill relished the opportunity to both travel and talk about the virtues of the NYSE auction market.

But my team and I knew our big opportunity to make a dent in the listings world would come that next June, when the Board had already decided and announced the NYSE’s then President, Dick Grasso, would assume the role of Chairman and CEO, replacing Donaldson.

Like any good communications and marketing team we developed a “First 100 Days” plan for Dick. But with a limited – at the time – advertising budget and Dick’s desire not to be gone from 11 Wall for more than a week (contrary to his predecessor who would spend two and three weeks on the road), we needed something special to reach the global business audience.

The answer we believed was television.

Since 1987, the NYSE had let credentialed television crews come into the Exchange and tape pieces (or do some live shots) from what was called the “Members’ Gallery,” a long thin walkway above the trading floor.

But in the plan we laid out for Dick, we wanted to let networks broadcast from the trading floor. It was – in essence – putting a “helmet cam” on the quarterback.

While it included what we hoped to do in his first 100 days, the plan was a five-year marketing initiative that we believed would elevate the Exchange to global prominence, creating a brand that would be unsurpassed in its space.

As I walked through the plan with Dick, he gradually began smiling and finally said, “It’s brilliant. But you convince The Animals.”

“The Animals” was our endearing term to describe some of the personalities on the “The Floor” (better known as the trading floor).

Convincing them was not easy. The Floor – at the time – was about 3500 people, a mix of specialists, traders, their clerks and NYSE employees. It was crowded, rough, but the greatest environment anyone could work in.

Loyalty…patriotism…a sense of doing what was important for business and America…is what The Floor was about.

But when I made my first stop – to the “Reds” – the members of the NYSE trading floor community who at the time were on the NYSE’s Board – they looked at me like I had just landed from Mars.

“You want those media people to be down here with us while we’re trading?” That comment came from Charlie Bocklett, a gravely-voiced specialist who at the time was an NYSE Board member and who commanded the respect of the entire floor. It immediately reminded me of the Mayor in Jaws saying to the Police Chief, “You want to shut down our beaches?”

Mike Robbins just looked at me, shook his head “no” and walked away.

But we kept talking and eventually got agreement to do a “pilot program;” one reporter would be allowed on the floor before the opening bell, but the reporter needed to be off the floor before the opening bell rang.

Next was contacting the business networks – the two significant ones in 1995 were CNBC and CNNfn. CNBC – at the time – was broadcasting from a perch above the floor of the now defunct American Stock Exchange.

Jack Reilly, a respected exec in television news, was the VP of News at CNBC, and a guy I knew well. I called Jack first because I thought he was the less likely of the two to do it. Lou Dobbs was running upstart CNNfn, and I assumed Lou would jump at the opportunity.

“Jack, here’s the deal,” I said. “The Floor and the Chairman have agreed to let a reporter broadcast from the floor before trading begins. It’s a pilot program, but I wanted to check and see if you’d be interested.”

“When could we start?” was Jack’s response.

“Next week?”

“Bob, I’ll call you tomorrow.”

I then called Lou Dobbs.

“Let me think about it,” was Lou’s response.

The next day, Jack Reilly called me back.

“Bob, we want to do it,” he said. “But I need to run something past you. The person we’d like to use is a woman. You probably don’t know her. Her name is Maria Bartiromo.”

I laughed.

“Jack, I know her well.”

When I was at Sony we would host over-the-top screenings of our upcoming movies for the media. Lou Dobbs would always be invited, but because his show on CNN aired at 7 p.m., Lou could never attend. Maria worked for Lou.

I had just started the screening of Damon Wyans’ Mo’Money in the summer of 1992 when security called me from the Sony Building lobby.

“Mr. Zito, there’s a Miss Bartiromo here who would like to come up to your screening.”

“Send her up.”

I told Jack that story and he laughed. “So, you’re OK with it?”

“Absolutely.”

And so it began.

Ray Pellecchia, Tony Walenty and so many other members of our team escorted Maria daily, until the floor agreed to let the networks broadcast “during trading.”

On the afternoon of CNBC’s first broadcast, Lou Dobbs called and said they wanted in as well.

That five-year marketing plan was completed in eight months, as by then we had 27 networks from around the world broadcasting from the floor.

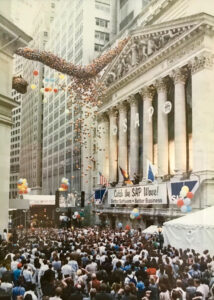

I had learned the power of entertainment at Sony, so we needed “programming” to keep the networks interested. We coached dozens of members to prep them to be on camera, and developed what we called the Partnership Program, which encouraged NYSE listed companies and member firms to host events inside and outside the Exchange, regularly closing Broad Street for events. Some attracted thousands to Broad Street. The celebration of SAP’s listing brought more than 20,000 people to our doorstep, and made it to the front page of the Wall Street Journal.

Ringing the bell became “the thing to do.” My personal favorites came during the last two weeks of 1999, and the first two of 2000, as we created the “Millennium Bell Series,” welcoming individuals who had made an impact on the 20th Century, and who would make an impact on the 21st. Muhammed Ali, Elie Wiesel, John Updike, Walter Cronkite, Bishop Tutu and others all came to 11 Wall to stand on our podium and ring that bell.

But the most significant bell in the NYSE’s history came on September 17, 2001 – the day trading resumed after the terrorist attacks of 9/11.

The flag we hung on our façade that day meant so much to all of us who came to that building every day. And it still does every time the Exchange hangs it.

The trading floor has changed dramatically. But the one constant for the past 25 years has been television. Still today, the NYSE’s significance and brand resonates daily around the world. It remains the pre-eminent marketplace in the world.

That’s all thanks to a CEO in 1995 who understood the power of a Brand…and gave us the green light to get it done.

Posted by Bob Zito on 6/18/2020